Fifty years ago Saturday, baseball lost a great player -- and a great man.

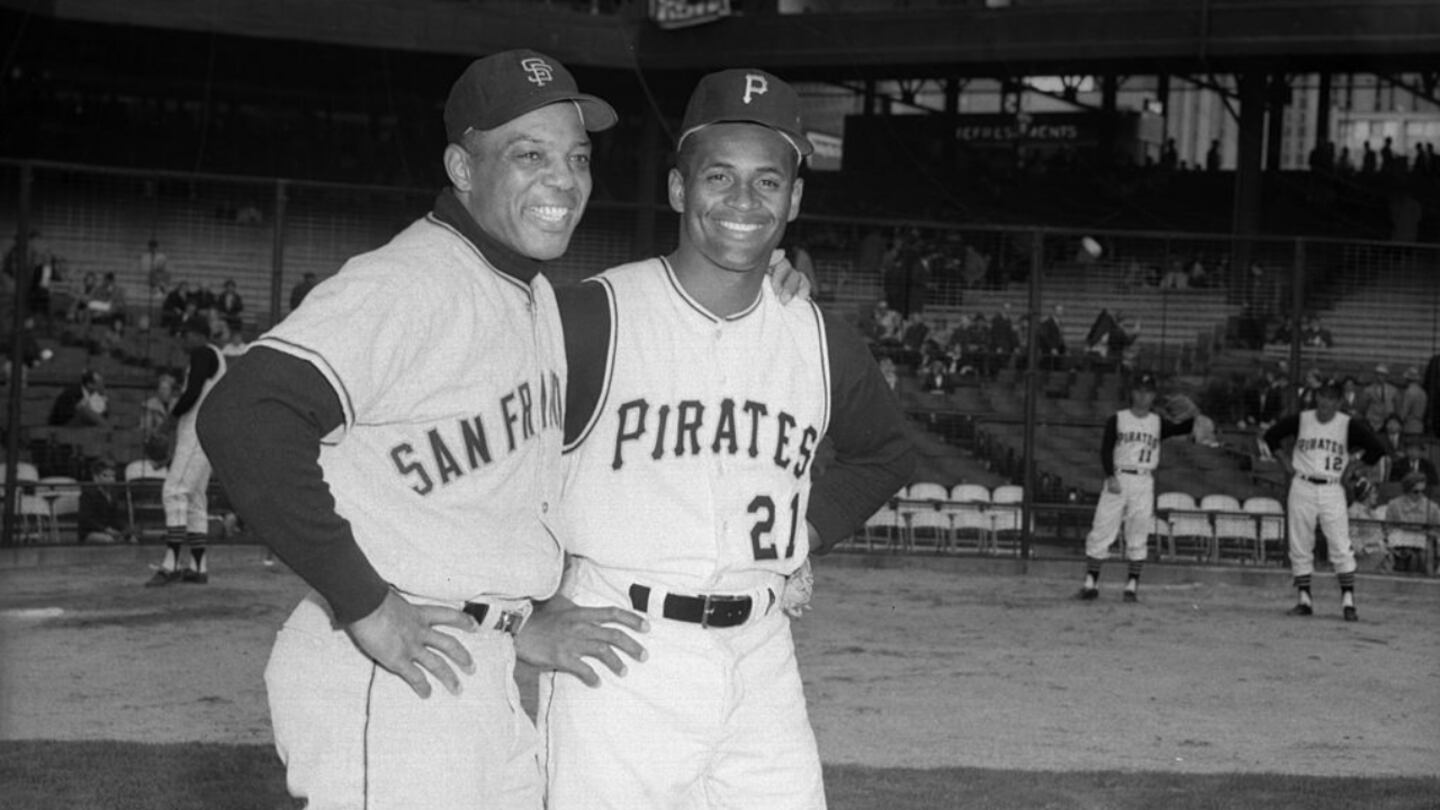

Roberto Clemente was known as “The Great One,” a prideful man from Puerto Rico who won four National League batting titles and two World Series crowns with the Pittsburgh Pirates. He was named to 15 All-Star teams, was the NL’s MVP in 1966 and won 12 straight Gold Gloves beginning in 1961. He finished with 3,000 hits, the 11th player in MLB history to achieve that feat.

Passionate and outspoken, Clemente’s humanitarian efforts showed a softer side. In a cruel twist of fate, Clemente’s charity led to his death at age 38.

On Dec. 31, 1972, Clemente boarded a plane in his native Puerto Rico. The four-engine DC-7 aircraft, chartered by the Pirates’ star right fielder, reportedly had a history of mechanical problems. The plane was overloaded by 4,200 pounds with supplies for earthquake relief to residents in the Nicaraguan capital of Managua and crashed into the Atlantic Ocean shortly after takeoff. Clemente’s body was never found. Four other people were killed.

Clemente had decided to follow the supplies to Managua after learning that some of the three previous shipments had been diverted by corrupt government officials in Nicaragua since the massive earthquake rocked Managua on Dec. 23, 1972.

Pittsburgh Pirates star Roberto Clemente is heading a committee to provide aid for Nicaraguan earthquake relief. pic.twitter.com/Pmoc8a0Hje

— 1972 Live (@50YearsAgoLive) December 28, 2022

“I think the thing that … that … well, I guess killed him, was his desire to do things for people,” Pirates general manager Joe Brown told UPI sports editor Milton Richman in January 1973. “What he was trying to do for the people in Nicaragua was one of the few public things he did.

“He generally did things, kind things, that few people knew about.”

Clemente was inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1973 in a special election that waived the mandatory five-year waiting period. He joined Lou Gehrig as the only members of Cooperstown to receive that exemption. Clemente also was posthumously awarded a Congressional Gold Medal of Honor in 1973 for his humanitarian efforts, according to Bleacher Report.

Here are some Clemente memories.

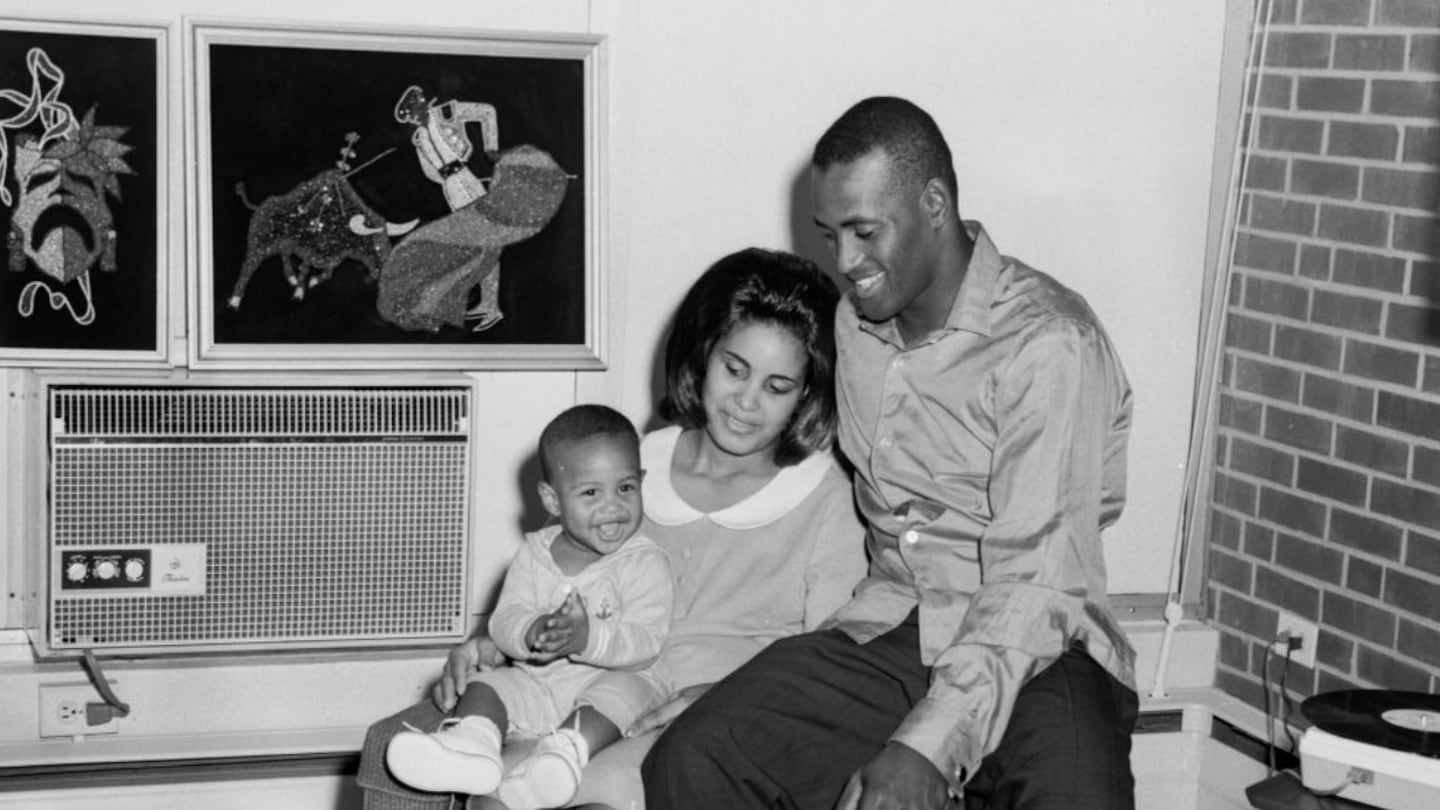

Personal life

Roberto Clemente Walker was born on August 18, 1934, to Melchor Clemente and Luisa Walker de Clemente in Carolina, Puerto Rico, according to the Society for American Baseball Research. He was the youngest of his mother’s seven children. Three of his older siblings were from a previous marriage.

Clemente married Vera Zabala (better known as Doña Vera) in Carolina on Nov. 14, 1964. They had three sons – Roberto Clemente Jr., Luis Roberto Clemente and Roberto Enrique Clemente.

Vera Clemente died in November 2019.

As a child, Clemente “had his own way of doing things,” David Maraniss wrote in his 2006 biography, “Clemente: The Passion and Grace of Baseball’s Last Hero.”

“He was pensive, intelligent, and could not be rushed. He wanted to know how and why.”

When asked to do something, Clemente would tell his family “momentito,” (just a moment) and said it so often that his older cousin, Flora, who took care of him, began calling him “Momen.” It was a nickname that stuck with Clemente among family, friends and the baseball fields of his youth, Maraniss wrote.

Getting to the pros

When he was 14, Clemente joined a softball team organized by Roberto Marin, according to SABR. Marin, impressed by the youngster’s arm, began using him at shortstop but then moved him to the outfield.

Three years later, Clemente was playing for the Santurce Crabbers of the Puerto Rican Baseball League. The Brooklyn Dodgers signed him in 1952, and by 1954 he was playing for the Triple-A Montreal Royals.

The Pirates claimed Clemente after the 1954 season in the Rule 5 draft, paying $4,000. He joined Pittsburgh’s parent club for good in 1955 and made his debut on April 17 at Forbes Field – against the Dodgers in the first game of a doubleheader.

Fifty years after losing Roberto Clemente, Channel 11 is looking back at his legacy. https://t.co/KTea4yvGCH

— WPXI (@WPXI) December 29, 2022

Clemente started in right field and went 1-for-4, scoring a run, according to Retrosheet.org. Wearing No. 13 – center fielder Earl Smith wore No. 21 early in 1955 – Clemente got an infield hit in the first inning when Dodgers shortstop Pee Wee Reese got his glove on the ball but could not field it cleanly. He scored the first of his 1,416 runs moments later when Frank Thomas tripled.

Clemente added two hits, including a double, and scored a run in the nightcap. The Pirates, however, lost both games.

Don’t run on him

According to Baseball-Reference.com, Clemente had 266 assists and participated in 42 double plays during the regular season across 18 seasons in the majors.

According to the Los Angeles Times, Clemente “was blessed with perhaps the strongest, most accurate arm of any right fielder who played the game.”

Clemente, who threw the javelin while in high school at Vizcarrondo High School in Carolina, said he inherited his strong arm from his mother.

“My mother has the same kind of an arm, even today at 74,” Clemente said during a 1964 interview. “She could throw a ball from second base to home plate with something on it. I got my arm from my mother.”

50 year anniversary of Roberto Clemente’s death 🙏🐐

— props.cash (@propsdotcash) December 30, 2022

pic.twitter.com/2ZF20j88U3

Here’s a sampling of the arm that gave runners pause.

On July 21, 1970, at the Astrodome, Clemente’s Pirates were facing Houston. Jesus Alou walked to open the home half of the first inning and Joe Morgan then sent a stinging line drive single to right field. Alou went to third on the play, and Morgan took a wide turn at first.

Bad move. Clemente threw behind Morgan to first baseman Al Oliver, who tagged the surprised future Hall of Famer out after he got caught in a rundown.

Even fellow Hall of Famers rarely challenged Clemente.

Maraniss recounts a memory shared by San Francisco Giants pitcher Gaylord Perry. Willie Mays was on second base in a tie game during the late innings. Clemente was in right field.

A teammate singled to right field, but “Mays rounds third and screeches to a halt,” Perry said. “When you have the world’s best base runner put on the brakes on a hit to right, you know it’s because the world’s best arm is in right. And it was a close game. We needed that run.”

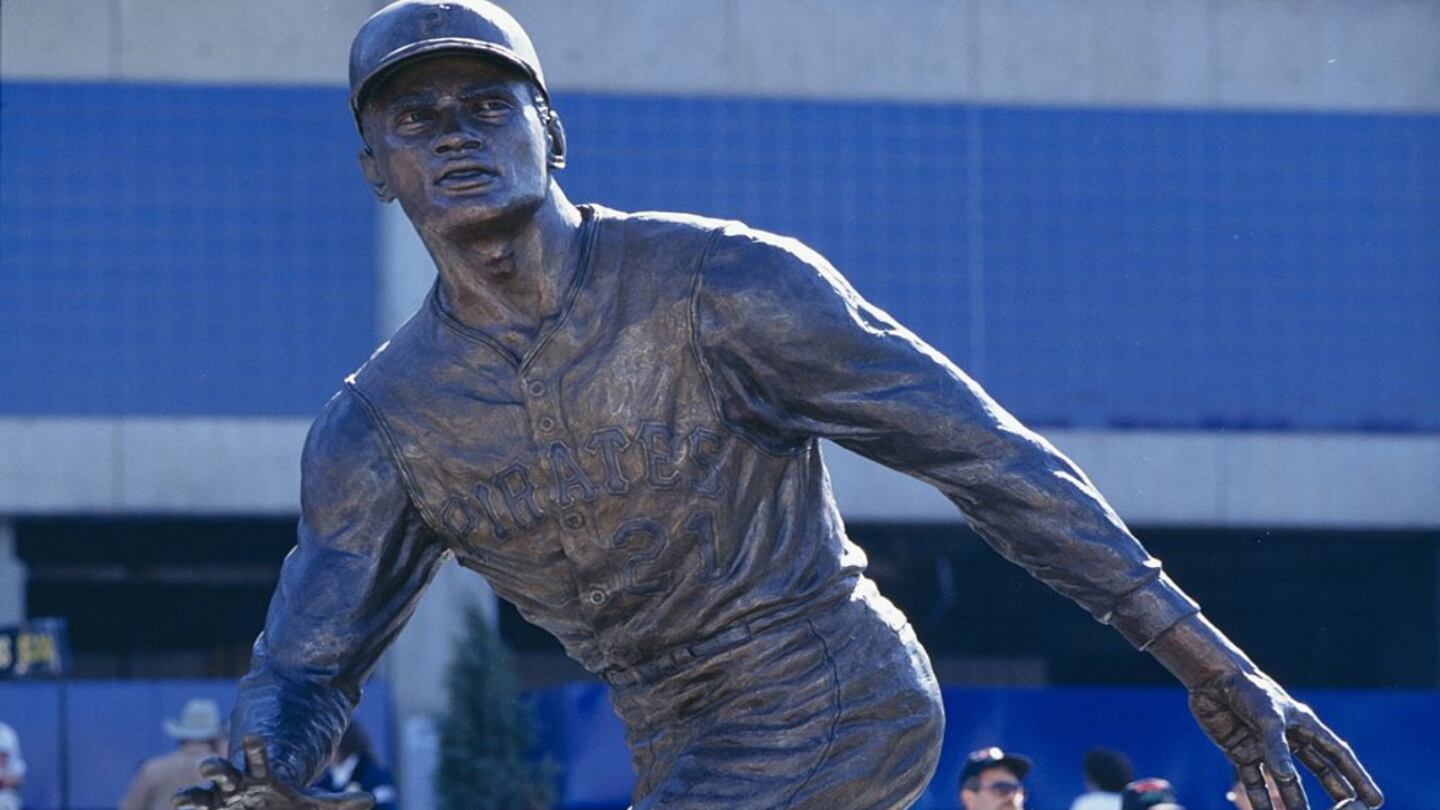

According to Bleacher Report, the right-field wall at Pittsburgh’s PNC Park is 21 feet high, which honors Clemente’s uniform number and his fielding position. While he played his home games at Forbes Field and Three Rivers Stadium, right field would always be Clemente’s domain. Woe to a runner who tried to test his arm.

“Clemente could field the ball in New York and throw out a guy in Pennsylvania,” legendary Dodgers broadcaster Vin Scully once said.

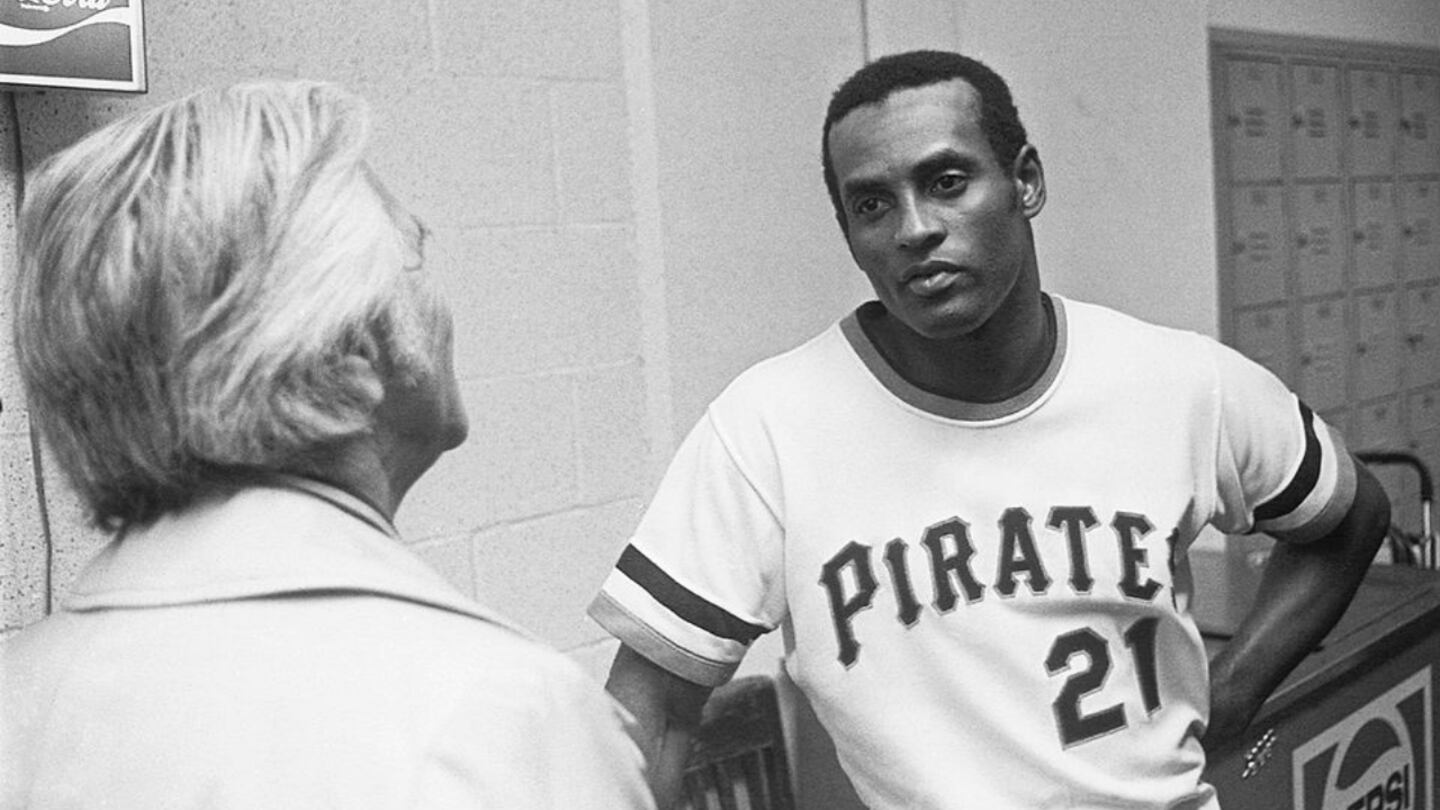

Battles with the media

Clemente never had a smooth relationship with reporters.

According to the Hall of Fame, some of that tension began in 1960, when he finished eighth in the NL’s MVP voting. Clemente had no issue with teammate Dick Groat winning the award, but he considered the eighth-place finish an insult, believing he should have finished higher in the balloting.

Clemente told reporters that his finish was due to “political reasons,” code words for his belief that racism against Latino players had a role in his low finish.

“He was convinced that it was due to that,” Luis Mayoral, a longtime writer, broadcaster and executive who also was Clemente’s friend. “To the day of his death, he was convinced of that.”

Sportswriters sent mixed signals in their coverage of Clemente.

Writers would ignore Clemente’s heritage and ethnicity, referring to him as “Bob” or “Bobby” instead of his given name. Even Clemente’s baseball cards listed him as “Bob Clemente,” a practice that finally ended with the 1970 Topps set. Topps referred to him as “Roberto” for his 1955 rookie card and his 1956 card, but from 1957 until 1959 the cards listed him as “Bob.”

What is your favorite baseball card of your favorite player? I’ll start with the 1972 Roberto Clemente whose @sabr bio is here https://t.co/u5oTZTjPLZ pic.twitter.com/FnPLr0AeCH

— SABR BioProject (@SABRbioproject) December 27, 2022

Clemente did not like the Americanization of his name, believing it disrespected his Puerto Rican and Latino roots. He would correct sportswriters during interviews.

Writers reluctant to use Clemente’s given name nevertheless quoted him and other Latino players phonetically. “This” was written as “deez,” or “give” was “geev.”

50 years ago this month, @Pirates and Puerto Rican baseball legend Roberto Clemente died while on an earthquake relief mission. Learn more about "The Great One's" life and legacy in new #SABR Digital Library essays, now available online: https://t.co/sJETdifnBA @ClementeMuseum pic.twitter.com/ylRRoMEJKW

— SABR (@sabr) December 26, 2022

“They laugh at me, but I heet the ball,” New York Daily News columnist Dick Young quoted Clemente as saying during the 1971 World Series.

Clemente believed that by highlighting his accent, writers were attempting to make him – and other Latino players – look foolish.

“It makes him sound like he’s dumb,” former Pirates pitcher-turned-broadcaster Nellie King once said. “And you know, he was a very intelligent man.

“I don’t know why the media did that. It sure made him seem less than intelligent. I mean, how would you like to go to Puerto Rico (speak Spanish), and have guys quote you the way you sound?”

Standing up

Clemente believed in helping those in need, and people who were victimized by discrimination.

“Dad knew he had a mission when he started playing,” Luis Clemente told the Times. “He always said that he was going to represent those that didn’t have a voice. … He knew he was representing the underdog in life and I think that resonated with many people. He was a real person and there was nothing fake about him.”

New Year’s Eve marks 50 years since the death of Roberto Clemente. His son, Roberto Clemente Jr., discusses his father’s life and legacy. pic.twitter.com/Ktdf15WRTJ

— Outside The Lines (@OTLonESPN) December 29, 2022

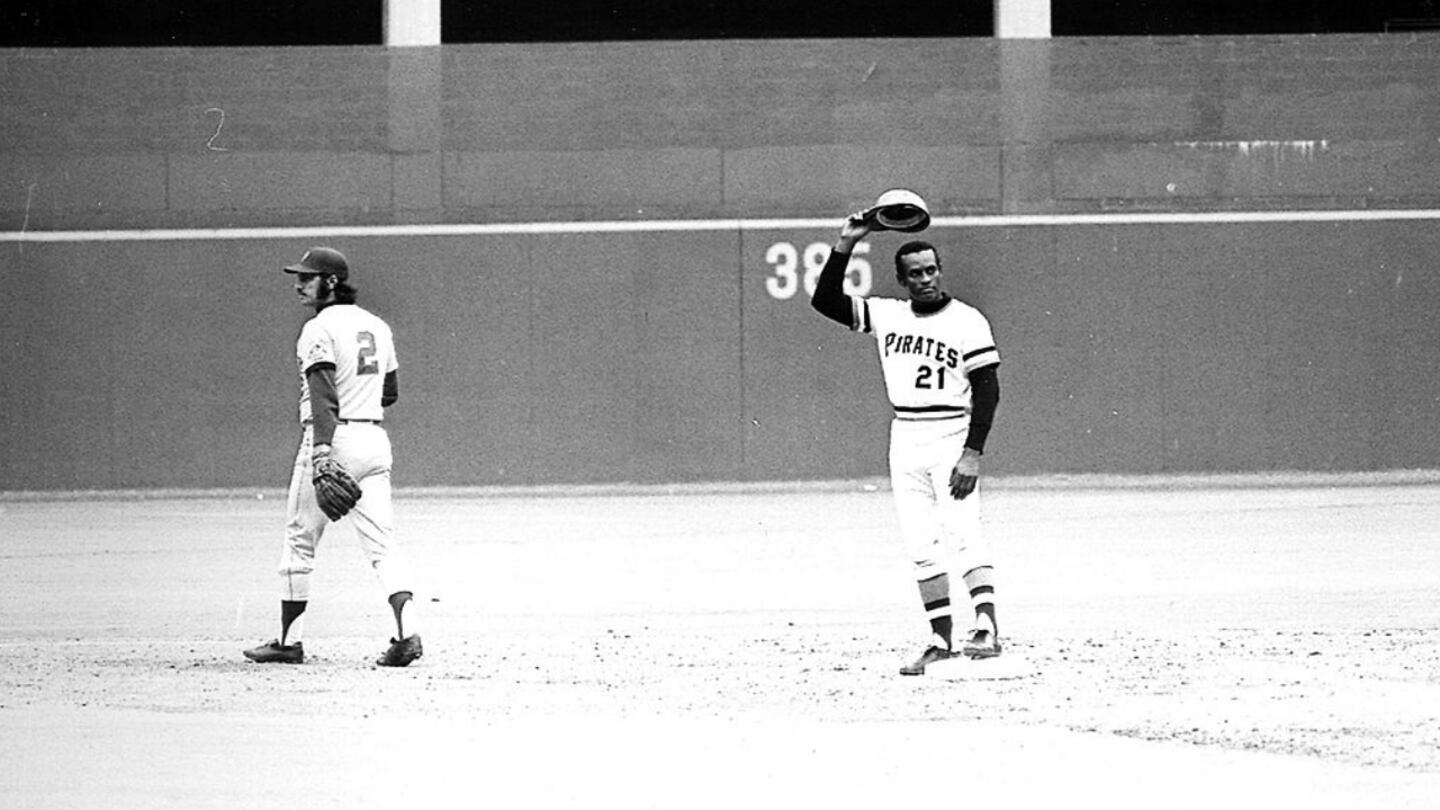

No. 3,000

Clemente connected for his 3,000th hit -- the final regular season hit of his career, when he doubled to left-center off New York Mets’ left-hander Jon Matlack in the fourth inning at Three Rivers Stadium on Sept. 30, 1972. He was the 11th player in MLB history to reach 3,000 career hits and the first player of Latino heritage to achieve the feat.

“I dedicated the hit to the Pittsburgh fans and to the people in Puerto Rico and to one man (Roberto Marin) in particular,” Clemente said. “The one man who carried me around for weeks looking for a scout to sign me.”

Remembering Roberto

Every season, MLB celebrates Roberto Clemente Day on Sept. 15. This year, the Tampa Bay Rays made MLB history by starting nine Latin American players against the Toronto Blue Jays, ESPN reported.

All nine starters for the Rays and base coaches Chris Prieto and Rodney Linares wore No. 21 to honor Clemente, according to the sports news outlet. They were from five countries – Colombia, Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Mexico and Venezuela.

MLB’s Roberto Clemente Award is given annually to the player who “best represents the game of Baseball through extraordinary character, community involvement, philanthropy and positive contributions, both on and off the field.”

Originally known as the Commissioner’s Award when it debuted in 1971, the name of the honor was changed in 1973 after Clemente’s death.

Each club reveals its annual nominee for the award on Roberto Clemente Day. The award winner is announced during that year’s postseason, according to Baseball-Reference.com.

Los Angeles Dodgers third baseman Justin Turner won the 2022 award, according to MLB.com.

Tremendous move inviting former Roberto Clemente award winners in New York on Sept. 15 to celebrate Roberto Clemente Day on the 50th anniversary of his passing. Here are the award winners who will be present. pic.twitter.com/4ozOYS0ZU5

— Bob Nightengale (@BNightengale) September 14, 2022

During his lifetime, Clemente wanted to build a “sports city” in San Juan, Puerto Rico. His vision was realized through the Roberto Clemente Foundation, started by Roberto Clemente Jr. The foundation “provides services and opportunities to children, families, veterans and underserved groups.”

What they said

“He gave the term ‘complete’ a new meaning. He made the word ‘superstar’ seem inadequate. He had about him the touch of royalty.” -- Baseball Commissioner Bowie Kuhn during a 1973 eulogy.

“Roberto Clemente gives dignity to the word hustler.” -- Dick Young, New York Daily News columnist.

“When Roberto Clemente dies, his body will hit .320.” -- Broadcaster Joe Garagiola.

“When he plays, he does it from the heart. He does everything that way.” -- Vera Clemente.

“When he threw a bullet to third, I threw a bullet to third. When he hit a home run, I wanted to hit a home run. He influenced me a lot and it drove me to be great.” -- Dave Parker, a Pirates prospect during Clemente’s final season.

“He was anything but perfect. He was vain, occasionally arrogant, often intolerant, unforgiving, and there were moments when I thought for sure he’d cornered the market on self-pity. Mostly, he acted as if the world had just declared all-out war on Roberto Clemente, when in fact it lavished him with an affection that few men ever know. (But I) know that through all of his battles … there was about him an undeniable charisma. Perhaps that was his true essence -- he won so much of your attention and affection that you demanded of him what no man can give, perfection.” -- Sportswriter Phil Musick.

“As a person, he’s irreplaceable.” -- Pirates fan James Horne, reacting to Clemente’s death in January 1973.

What Clemente said

“If you have a chance to accomplish something that will make things better for people coming behind you, and you don’t do that, you are wasting your time on this Earth.”

“If I could sleep. I could hit .400.” -- Discussing his insomnia.

“I am more valuable to my team hitting .330 than swinging for home runs.”

“Why does everyone talk about the past? All that counts is tomorrow’s game.”

“When I put on my uniform, I feel I am the proudest man on earth.”

Final plate appearance

Four days before his death, Clemente held a youth baseball clinic in Puerto Rico, the Times reported. He decided to bat against a teenage pitcher, and fans in the stands challenged the Pirates’ star to hit a home run.

On the fifth pitch, Clemente hit a 350-foot home run, according to the newspaper. It was the final at-bat of his life. Clemente gave the pitcher his bat as a souvenir, said goodbye to the players at the clinic, and then prepared for the final trip of his life, the Times reported.

FIFTY YEARS AGO: Roberto Clemente conducted his FINAL baseball clinic for 300 kids in Aguadilla, Puerto Rico at Parque Colón. He even hit a 350 ft blast over the left field wall. It would be his FINAL HR.

— Talkin' 21 (@Talkin21podcast) December 27, 2022

Our next Talkin' 21 episode: A former Pirates infielder. And he was there. pic.twitter.com/ds3s993ifh

“He has become almost a saint,” Amaury Pi-Gonzalez, vice president and co-founder of the Hispanic Heritage Baseball Museum Hall of Fame, told the newspaper. “Because of the way he died and his body never being found, he lives forever in the minds of the fans.”

Information from newspaper archives was used in compiling this report.

©2022 Cox Media Group