A mission to outrun malaria became a booming citrus venture.

In the mid-1800s, one of the first founders of Ocoee came to the rural area to avoid the outbreaks of the mosquito-borne disease. Ocoee was not yet established as a community, but white settlers saw it as an area of opportunity.

“They came here with the slaves that they owned to try and be somewhere distant from other people and protect themselves from the outbreak,” said Melissa Fussell, who, in 2016, published a William & Mary Law Review paper on the ramifications of the 1920 Ocoee massacre.

One of those settlers was a man named J.D. Starke. He arrived with 23 slaves. Attracted by Lake Apopka, he settled along what would become Starke Lake. Starke had served in the Confederate Army and returned to Florida following the war. He sold some of the land to Captain Bluford Sims. Sims, also a veteran of the Confederate Army, relocated to Florida from North Carolina. He built a home along Starke Lake and started growing and selling citrus by the 1870s.

Florida was attractive to early settlers because of its vast land and the fruit of opportunity that would become a cash cow for the state’s agricultural business. The sandy soil and the climate were prime for citrus farming. Today, the state still celebrates it as a $9 billion industry, responsible for providing jobs to nearly 76,000 Floridians and 70% of the supply in the U.S. comes from Florida. Globally, the only other place producing more orange juice than Florida, is Brazil. And Florida leads the market in grapefruit production.

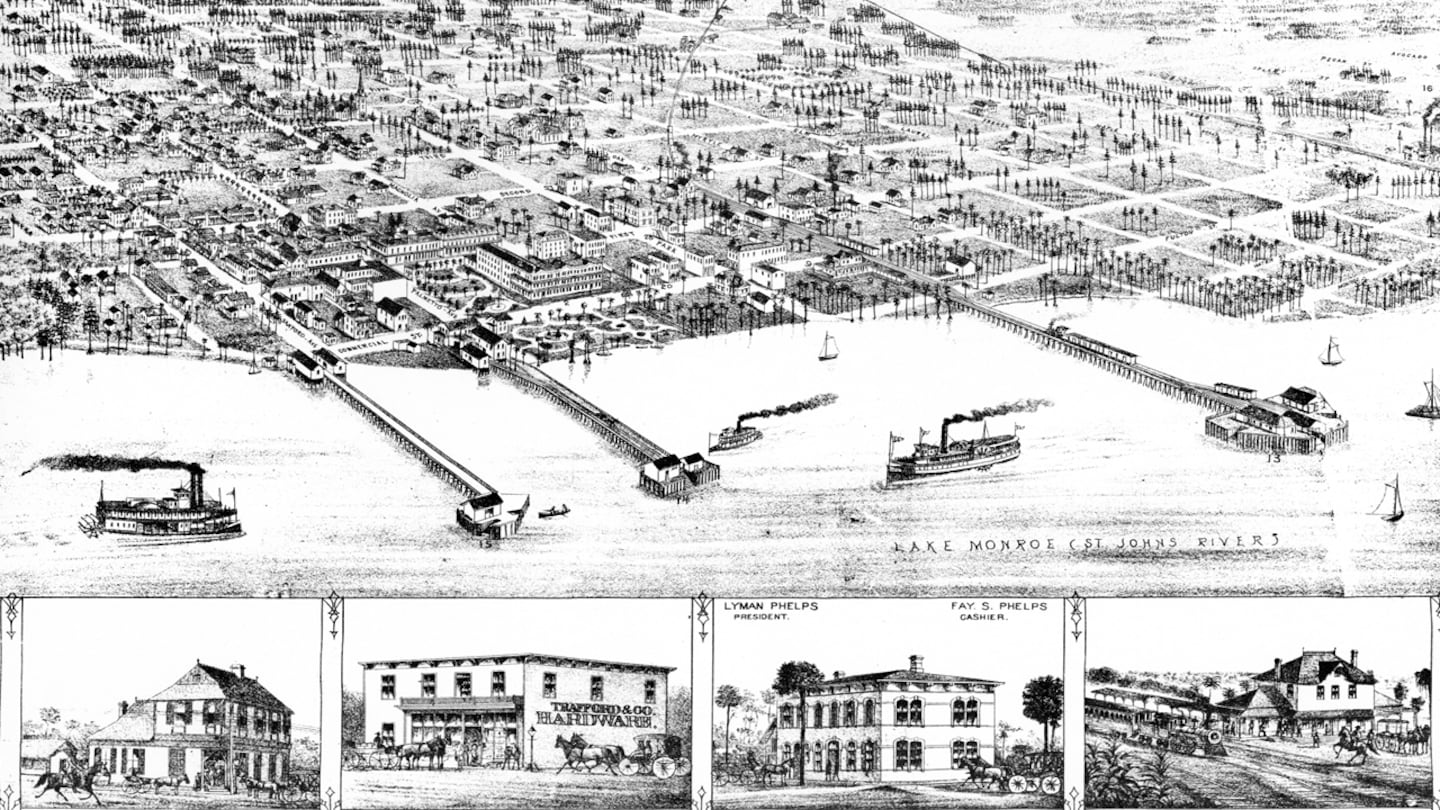

Back in the mid-1800s, the closet shipping port was in Sanford; it made for a long commute from West Orange County during those times. Transport, though, got easier when Florida Midland Railroad made its way to central Florida.

Just as whites were eyeing the opportunity citrus afforded, Blacks were looking for equal promise. Families made their way from other southern states like Georgia and South Carolina, where they had been picking cotton. Picking citrus was simply more lucrative and less taxing work.

“Lake Apopka was the key. Whoever discovered the richness of the land, the soil… as I was told once by my grandmother, you can make more money picking citrus than you could picking cotton. With cotton you would probably 40 cents on a 100 pounds. That’s a lot of cotton for 40 cents. You could pick oranges by the box sometime at 75 cents a box. So, oranges or citrus was the main thing for early Black settlers,” said Francina Boykin, member of the Democracy Forum and Apopka Historical Society.

“The white man was trying to sell them, old swampy land that they thought was no good.”

— Gladys Franks Bell

When Blacks settled in Ocoee, they didn’t come looking for a handout, but obtaining good land that afforded them an equal opportunity in the agricultural business was difficult. Despite the hopes and dreams for a better life in Florida, not all was perfect for Blacks who moved there. White profiteers attempted to exploit them. “The white man was trying to sell them, old swampy land that they thought was no good,” said Gladys Franks Bell.

Her father, Richard Allen Franks, settled in Ocoee.

“I can only go by what my dad, you know, told us that, they had money. They [were] able to go to the market and, and buy the best horses, the best cows, because by them moving from South Carolina, they had experience of selecting.” Their experience and knowledge about farming made their ventures profitable. They bought the land the white salesmen thought was useless.

“They knew how to cultivate that land, how to drain it, how to plant orange groves there, how to prep the vegetables,” Bell said.

Black settlers saw opportunities where others did not.

“The biggest thing is they would build a home and they would just start whatever their entrepreneurial pursuit happened to be” said Pam Schwartz, a curator for the Orange County Regional History Center. “In this area, it was largely citrus.”

From its inception, Ocoee had a small Black population. By the early 1900s several hundred Blacks were recorded in census data among a population of just under a thousand total residents.

“Most of the families who had been formally enslaved here, as best we can tell, leave fairly immediately,” Schwartz said. “By 1870, there are 11 Black adults living in the area. They are mostly working for white employers. By 1885, that number is up to 15 adults and then it just slowly rises in numbers beyond that point.”

Black families settled in two communities. They were on opposite ends of what is now downtown Ocoee. The center of the Black communities, as it often is now, was the churches. The area known as the Southern Baptist Quarters was formed near Friendship Baptist Church, which was founded around 1896. The other was the Northern Methodist Quarters, developed on land near the African Methodist Episcopal Church, founded in 1890. Members worshipped in private homes until about 1895 when the first and last buildings were erected. The earliest known clergy were Rev. M.M. Gaines and Rev. R.L. Jones.

“In Ocoee itself, you are looking at a larger white population than a Black population, but you do have a variety of individuals from mixed backgrounds,” Fussell said. “There are individuals of Seminole background living here along with other demographics as well.”

“Property means, you aren’t just working for somebody else.”

— Pam Schwartz

Moses Norman and Valentine Hightower were among the first to buy property.

“That starting around 1888 to 1892. They (early Black settlers) had their own pursuits, but largely they were working for white employers when it came to agriculture specifically and they just saved,” Schwarz explained, “and when they had the opportunity, they started buying property. And of course, property means, you aren’t just working for somebody else. You can also have your own income coming in through agricultural pursuits or otherwise,” Schwartz explained.

Julius ‘July’ Perry moved to Ocoee from South Carolina. He settled in town and earned a living through the farming, becoming, a powerful businessman.

“He first came to Jacksonville, then to Apopka, and eventually found his way to the Ocoee area, purchases property, early 1890s,” Schwarz said, “I believe is his first, purchase in this area … and also came to be known as a labor broker.”

“He certainly was not somebody who in any way was defensive of the Black community.”

— Melissa Fussell

Ocoee’s white community had deep ties to the Confederacy. Dr. J.D. Starke, who survived the war, returned to Ocoee along with other Confederate veterans. Among them was Captain Bluford Sims.

Sims became one of the town’s most successful white residents. He made his money in citrus farming. He held various government positions, Fussell said. To this day, his name is revered; the main corridor through town bears his name. The local chapter of the Sons of Confederate Veterans is named in his honor.

“He certainly was not somebody who in any way was defensive of the Black community,” Fussell said.

The state of Florida recognized the town of Ocoee as a municipality in 1923. It was established as a city in 1925, five years after the massacre that would drive every Black person out of town. Some were killed, one even lynched, before their communities were torched by fire.

Cox Media Group