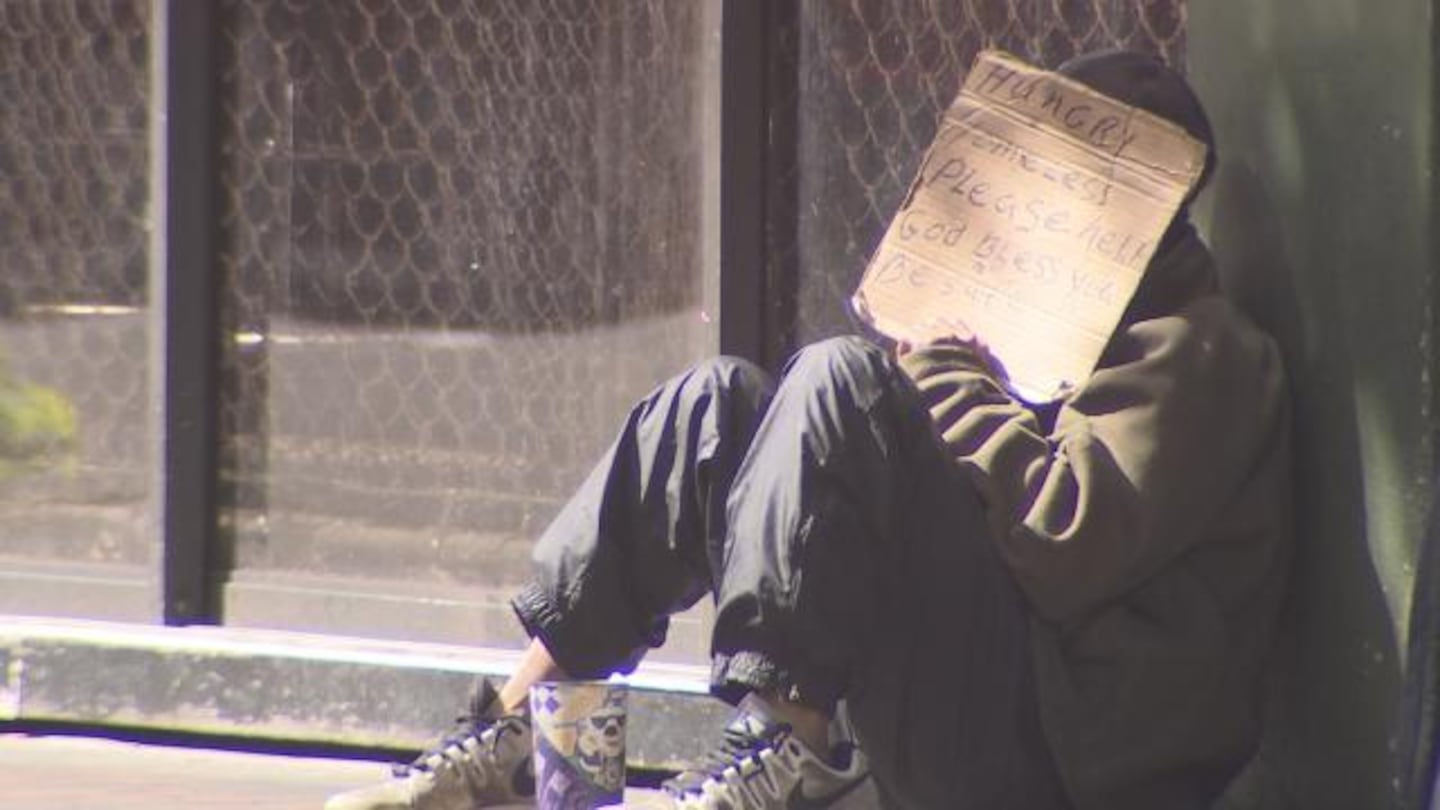

ORLANDO, Fla. — They are a common fixture of downtown Orlando street corners and Lake Eola park benches. Thousands of people walk or drive by them and their cardboard signs and paper cups every day. But few stop to ask how they got there or why -- until now.

For more than a year, advocates teamed up to find out how many panhandlers there are in downtown Orlando, how they got there and what city leaders can do to help.

The first-of-its-kind study, called “Understanding Panhandling,” set out to see if panhandling is really on the rise despite an 11%, three-county drop in homelessness since 2013.

TRENDING NOW:

- Police: Woman dies following triple shooting on Orlando intersection

- Martie Salt retires after 40 years of keeping Central Florida informed

- Squirrel caught on video stealing package from porch

- Florida man found partially eaten by alligator died from meth overdose

It revealed that of the 300 to 400 homeless people in the area, just 15% to 20% of them actually do the majority of the panhandling.

The study states there are 61 people who chronically panhandle in downtown Orlando. Among that group, 82% are chronically homeless, and some have been so for more than 20 years.

“These individuals panhandle on average six hours a day, six days a week on the streets every single year, interacting with individuals,” said Andrae Bailey, CEO of changeeverything.com and founder of Rethinking Homelessness.

The study, which was completed by representatives from Rethinking Homelessness and the HOPE (Homeless Outreach Partnership Effort) Team at the Health Care Center for the Homeless in partnership with the University of Central Florida, showed that for those 61 people, panhandling is a full-time job.

Of the group of 61 regular panhandlers, the study states that 58% have a mental illness and 92% have a substance abuse disorder.

Of the panhandlers researchers interviewed, they reported collecting an average of $63 per day. With that money, they reported spending an average of $75 per week on alcohol and $59 a week on drugs. The rest, the study said, is often spent on food, water and hygiene products.

“(If) you give someone money who is panhandling, most likely, that money’s going to be spent on drugs and alcohol,” Bailey said. “That is not a solution to that person’s problem.”

The study also looked at how other cities are addressing panhandling. Bailey said researchers pointed to the homeless response system used by the city of Miami, which includes mental health intervention, as an example.

Bailey said the city is using the Baker Act to commit homeless people with mental illness who don’t seem willing on their own to get help. By doing so, he said, they can get medications and treatment.

“It's absolutely working,” he said.

READ: Daytona Beach homeless shelter opens following years of delays

The research also suggests neighboring cities and counties with conflicting panhandling rules and ordinances only compound the issue.

“You're going to draw panhandlers and people living outside to certain parts of the community, so uniformity is something that should be looked at,” Bailey said.

Bailey said he'll be sharing his findings with community leaders in the coming weeks.

To get a complete look at the findings, watch Channel 9 anchor Greg Warmoth interview Bailey on “Central Florida Spotlight” airing Dec. 22.

© 2019 Cox Media Group